HMC Collaborative Research "Digital Platform for Cultural Resources for Open Humanities Inariyu Nagaya Restoration and Regeneration Virtual Archive Companion Site

In this collaborative research project of HMC, we are conducting basic research towards the construction of an open digital platform for cultural resources.

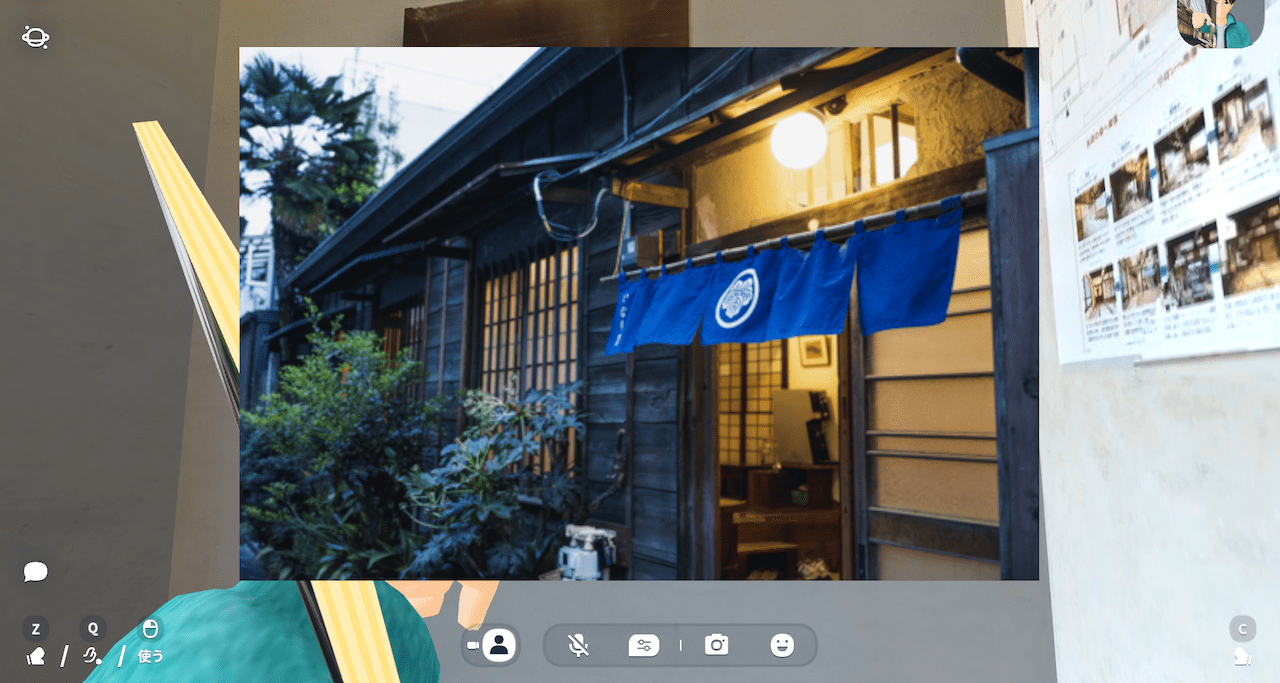

As part of this project, we have been working with Sentō to Machi, a general incorporated association that is working to regenerate and revitalize the "local ecosystem" centered around public bathhouses, to create a virtual archive (hereafter referred to as "VA") of the project to restore and revitalize the "nagaya" (two-house tenement) adjacent to Inariyu in Takinogawa, Kita-ku, Tokyo.

We hope that VA, its website, and the book list will provide some inspirations and ideas for collaboration between the humanities, informatics, architecture, and urban development to regenerate and revitalize our local ecosystems.

PS: In 2024, the Inari-yu Bathhouse Restoration Project has received UNESCO's highest recognition, the Award of Excellence in the 2024 UNESCO Asia-Pacific Awards for Cultural Heritage Conservation.

Click here for the Inariyu Restoration and Revitalization VA.

- The Origin and Work Process of the Inariyu Nagaya (Two-room Tenement) Restoration and Revitalization Virtual Archive (Yusuke Nakamura)

- Main work, results, and issues

- Intellectual Property Rights for this Project

- Member

- Acknowledgements

The Origin and Work Process of the Inariyu Nagaya (Two-room Tenement) Restoration and Revitalization Virtual Archive (Yusuke Nakamura)

Inariyu Restoration and Revitalization VA is an action research project that addresses the question of how to combine print and digital technologies to support the revitalization and regeneration of local ecosystems, starting with the restoration of Japanese traditional architecture.

The starting point for the creation of this VA was the huge number of photographs and records of the restoration and revitalization work on the nagaya that Sentō Machi has been working on since 2019. The full story is recorded in the "Inariyu Restoration Project" report (95 pages, full color, in Japanese and English, published in June 2024), which includes not only the details of the restoration work, but also the history of the Inariyu and Takinogawa areas.

We thought that if we could create a virtual reality (VR) space that included photos and explanations of the construction work, along with the report, it would serve as a virtual archive (VA) enabling more people to share in the restoration and revitalization process, and would also provide valuable suggestions for people with similar aspirations.

In fact, commercial services for the creation of VR spaces are already widely available, and even end users with little expert knowledge can try out various ideas using VR technologies. The appeal of VR that makes full use of digital technology lies first and foremost in the fact that it allows us to design light, sound, depth and motion with a freedom that would be impossible in the real physical world. This is a big difference from the feel and tranquil appearance of the mainly black-and-white print pages that have supported traditional academic research. It provides an opportunity to challenge new academic research and its expression. And, we were fortunate to be able to receive service free of charge from Cluster, Inc. as a research activity.

Graduate students from a variety of fields, including architecture, archives, cultural resources studies, and digital humanities have participated in the construction of the VA. In addition, the virtual world was created by Panda Mole, a VR artist who already has a wealth of experience in town planning using VR technologies.

The work began with a 3D scanning of the nagaya in the summer of 2023, followed by the creation of the VA. For many of us, this was our first experience dealing with a full-fledged virtual 3D world. But as we progressed with the arrangement of photos and explanations, we became more familiar with the VR space, and began to come up with new ideas for expression. The result is this VA that incorporates some of the playfulness unique to VR technologies here and there.

We also decided to create a bilingual VA in Japanese and English so that the challenges of the Inari Yu Nagaya Restoration and Renovation Project could be shared widely beyond Japan.

On the other hand, through our experience creating VA, we have come to realize once again that printed books, websites, and VR each have their own charm that is difficult to replace with other media.

Based on this realization, we created this companion site, which places emphasis on the multimodal and interactive design that is unique to 2D website technologies. This site also lists many more recommended Japanese books than in the VA.

While we were nearing the end of the VA creation process, in the summer of 2024 we knew that one of the buildings around Inariyu was to be demolished. Towns are constantly being reborn, but we wanted to record the current appearance of the area around Inariyu as much as possible. Fortunately, Tokyo Cable Network Co., Ltd. kindly cooperated with us and gave us the opportunity to try out their latest digital equipment. Therefore, although it goes beyond the scope of this Inariyu Nagaya VA construction, we carried out the digital scanning of the surrounding streets at the end of August with the hope for future use.

Below are the main tasks, achievements, and challenges for each item.

Main work, results, and issues

World (Panda Mole)

First, we used 3D scanning to capture the real space and convert it into CG, and then rebuilt the CG objects according to the measurements. At first, we were mainly thinking about déformer, but when we saw the atmosphere of the actual place, the attention to detail in the materials, and the craftsmanship, we changed our policy to preserve the actual objects as much as possible. Normally, the same type of object, such as a wall or a pillar, would use the same texture to reduce unnecessary memory usage, but this time we used the original textures as much as possible, and we valued the individual expressions of the pillars and walls. The world was created in cluster using the dedicated SDK, CCK (Cluster Creator Kit) and the game engine Unity. We didn't try anything new beyond our previous experience, such as UI display gimmicks, but the perspective of the architecture and archives was something new, and the approach of giving a single space different faces was a precious learning experience.

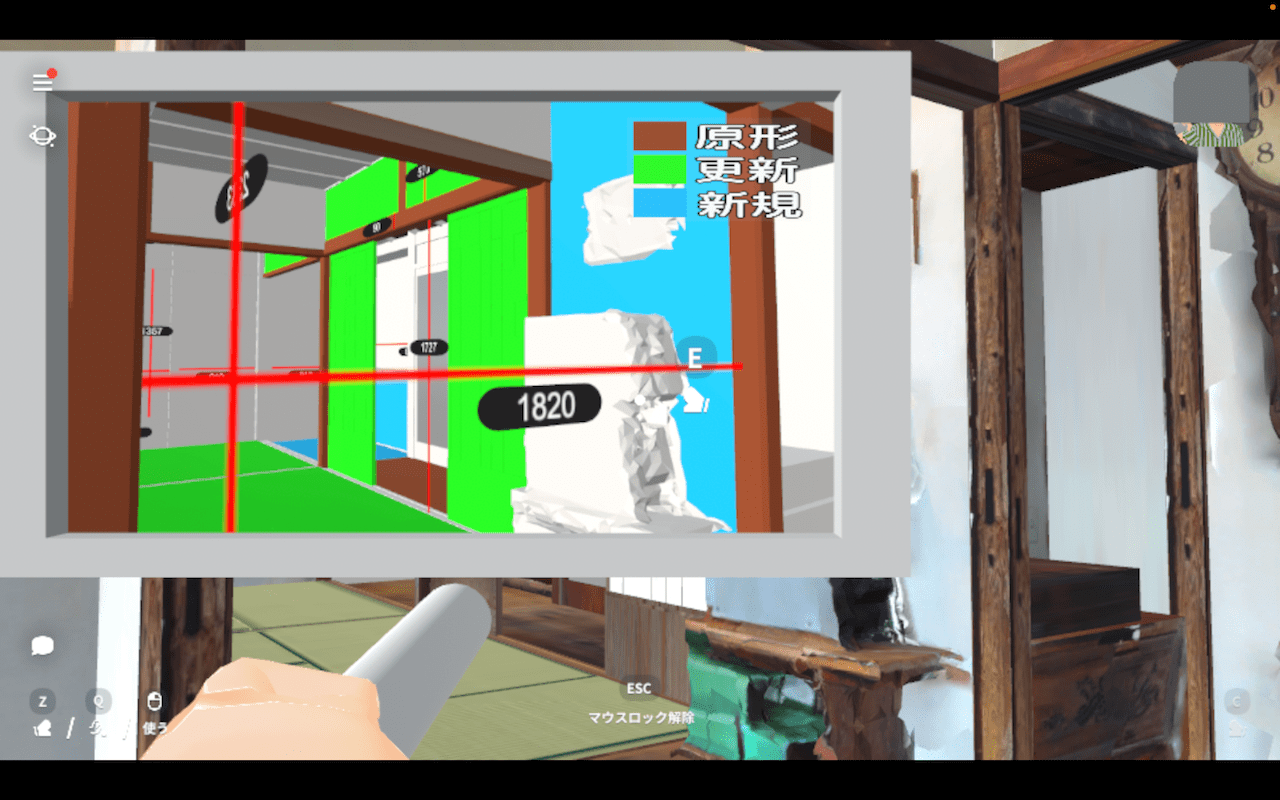

One of the challenges was the relationship with actual size, which we don't usually think about in a metaverse. For one thing, the average height of the avatars is lower than the actual one. In addition, the existence of a third-person perspective. Apart from when using HMDs, in metaverses users tend to use TPV (third-person perspective) rather than FPV (first-person perspective). The third-person perspective is used to see the avatar from an angle behind, so there is a need for extra space, and if it is made the same size as real life, it will be difficult to see the contents. In our case, the ceiling is slightly low. So we decided to make the dimensions 1.2 times the actual size, because it would be difficult to operate the TPV at actual size. On the other hand, from the perspective of architecture, accurate dimensions are important, so this gap was one of the issues we had to address. In this project, we tried to solve this problem by adding a dimension display that can be turned on and off in the "Layer Viewer".

For further details on worldbuilding from an architectural perspective, please refer to the Restoration and Reclamation section.

Restoration and Revitalization (Seishi Watanabe and Takako Fujimoto)

In this project, the restoration and revitalization work and the creation of the virtual archive were carried out by two different organizations. The restoration and revitalization work and the recording of the restoration process were carried out by the general incorporated association Sento to Machi, and the virtual archive was created by this project. However, here we will introduce the work processes and important points involved in creating the archive for those who are mainly interested in creating a virtual archive while also restoring and recreating the archive.

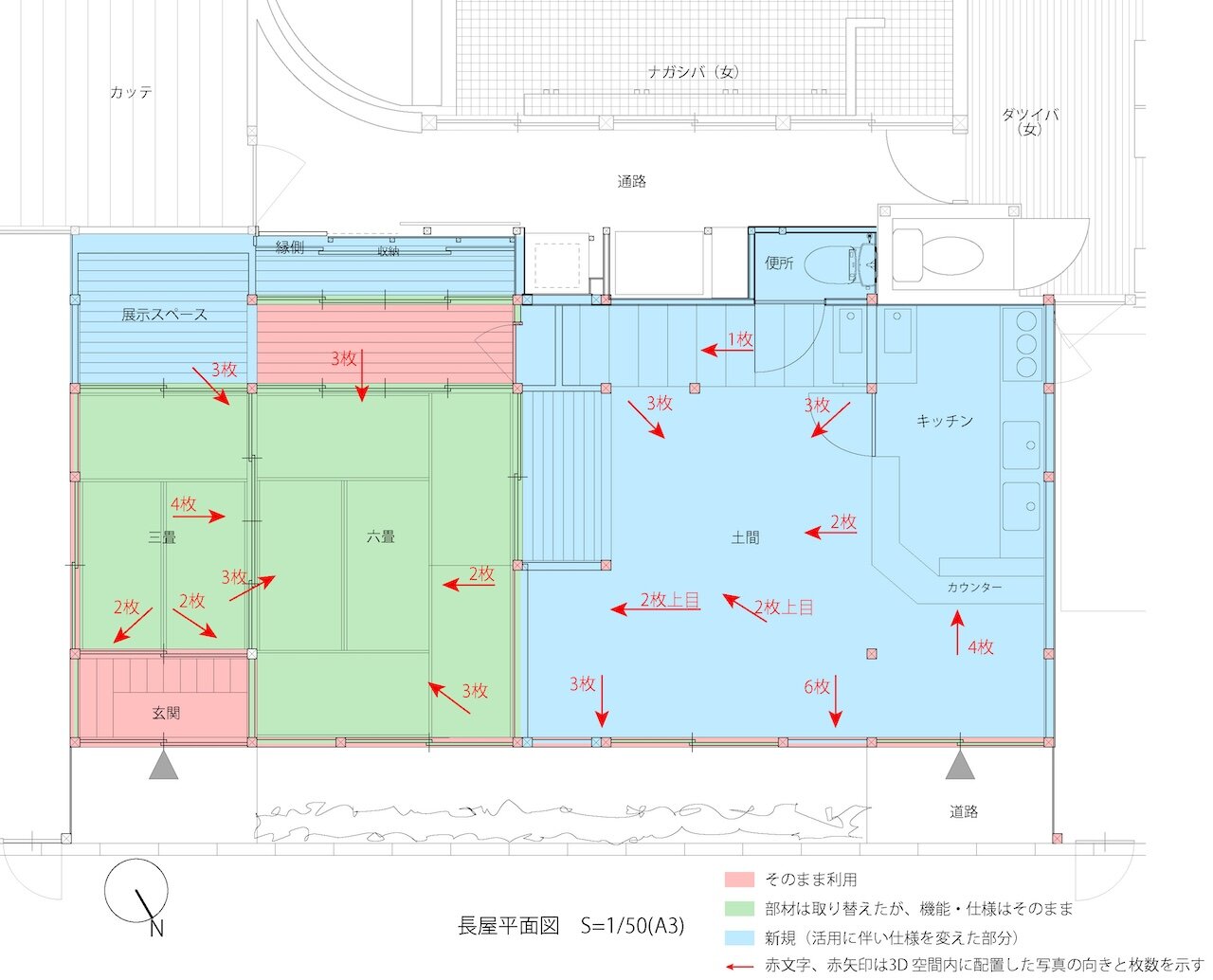

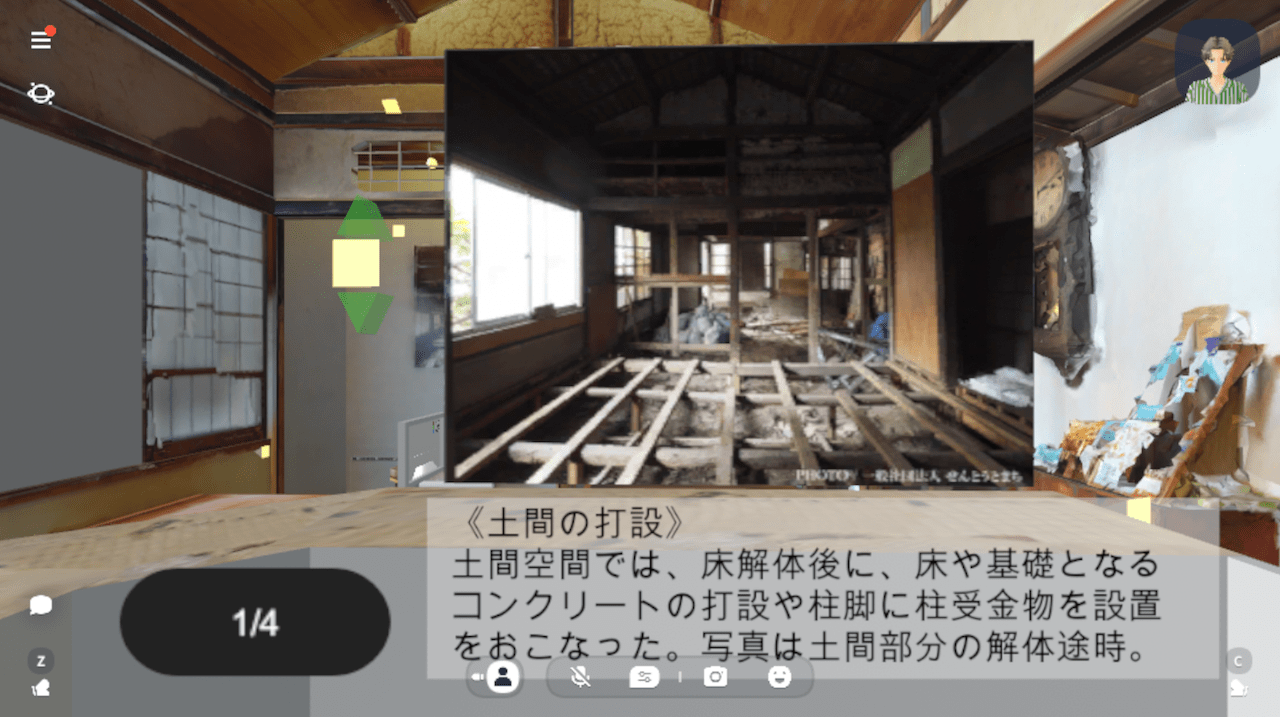

First of all, the main work and also a very important process during restoration and reproduction is the recording of text and photographic media. In particular, since we received external funding for the restoration of the text media, we recorded a lot of the restoration content and process, and compiled the content into a report. In this project, we mainly used this report as captions when creating the 3D content. In addition, many photographs were taken by the photographer and by each member as a record of their work. The photographs taken by the photographer, taken from a fixed wide-angle position, showing "before restoration", "during restoration" and "after restoration", were extremely useful for showing the changes that took place. In particular, as it is only possible to take photographs before and during restoration at certain times, it is important to record as much as possible.

Also, when taking photographs, it is important to keep track of where the photographs are, when they were taken, and who took them. If you take a large number of photographs, it is important to keep them organized so that you can easily use them when creating the 3D model.

Next, the main tasks involved in creating the virtual archive are as follows.

1) Within the completed world, we placed fixed-point photos that show the changes from before and after restoration, as well as photos taken during the restoration process. When placing the photos, we selected the most easily understood photos from among the many photos we had taken, and placed them carefully, paying attention to the direction in which they were placed. In this case, as there were so many photos to place, we created a gimmick that displays photos by performing an action on an icon, and made the icon a pyramid shape to clearly indicate the direction. In addition, we made sure that the photos could only be viewed from one side to avoid confusion. Furthermore, we inserted credits into the photos beforehand to clarify the location of the work.

Viewing angles and number of images placed within the world

First-person view inside the world

2) We then created the photo captions. In this case, as we had the report, we extracted most of the text from it and used it to compose the captions. When composing the text, we decided that the number of characters displayed in the UI should be around 40-60 characters (two or three lines), and we also made it easy to understand by including the name of the process in the first line. In addition, we decided in advance who the text was intended for, and this time we composed the text in a simple way that even beginners in the field of architecture could easily understand.

Display captions for images

3) We used a gimmick called "Layer Viewer", which uses color coding to show the age of the building materials, and divided the space into three colors to show the difference between "original", "updated" and "new" materials. We made it so that you can see which materials were used as they were, which materials were replaced, and which materials were newly created, by moving around the space. Within the layer view, we also added a gimmick that displays the overall pillar spacing and ceiling height by taking further action, so that the dimensions can be seen at a glance even within the 3D space.

Example of using the Layer Viewer

Finally, we would like to make one point clear: because the avatar size could not be set in the cluster we used this time, there was a problem where the size and feeling of the space in real space was slightly off. In response to this, this time we tried to eliminate the difference as much as possible by using the scale display in the layer view, placing the finger rectangles, and arranging the floor plan.

In the future, if it is possible, we can expect to make an even greater contribution to architectural education if we can eliminate this difference.

Ambient Sound (Shintaro Seki)

The media experience of entering a VR space while wearing a head mounted display (HMD) is experienced through the mobilization of our perception of the four-dimensional space-time we live in on a daily basis. It is understood by everyone that you cannot hear sound from a two-dimensional photograph, but it would be an exaggeration to say that there is no environment in our daily lives where there is no sound at all, except in specially prepared anechoic chambers. When we checked the completed initial 3D model, it became clear that the absence of sound filling the space was experienced as a greater sense of discomfort than we had initially assumed, especially in terms of perception of the 3D space with the HMD on. Our investigation into the placement of environmental sounds began with this sense of discomfort.

Immersion and Sound in Virtual Space

The phrase "perceptual illusion of nonmediation" is a key phrase in immersive content, including VR. This phrase, which Matthew Lombard and Teresa Ditton proposed in 1997 as a definition of "presence", vividly points out that the feeling of "being there" can be positioned as a state of illusion of the absence of media such as displays. Around the same time, Jay Bolter and Donald Norman were also developing discussions on "media transparency" in the context of UI design and media art, but the points made by Matthew and Teresa, which seem to have predicted the current spread of remote communication through online conferencing systems and VR, continue to be referred to as being full of suggestions. From the 1990s, when the first VR boom occurred, to the present day, it can be said that VR technology has developed around the pursuit of this "perceptual illusion of nonmediation".

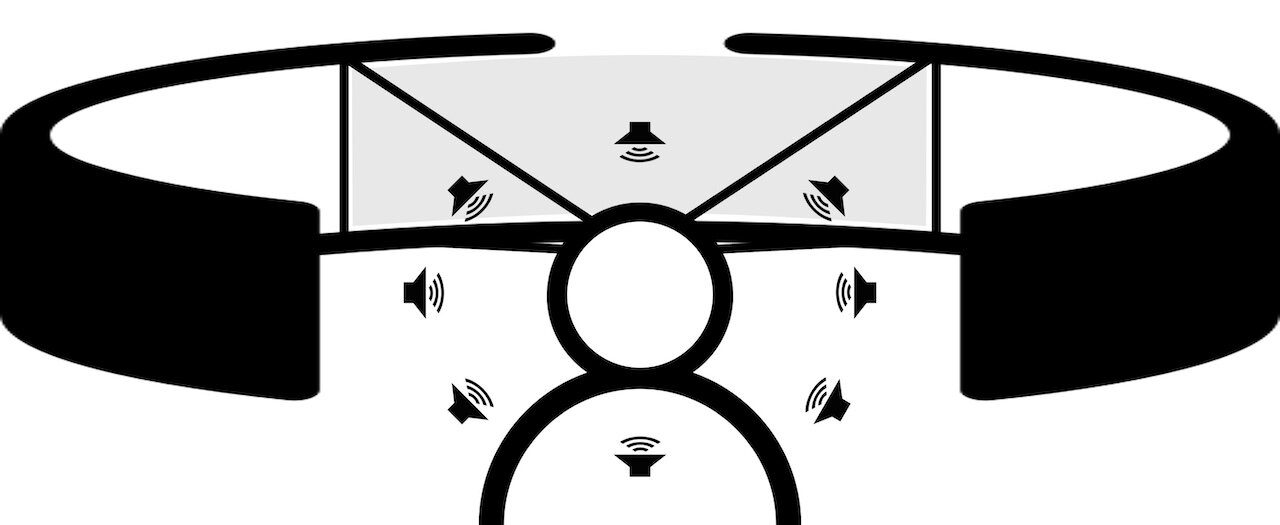

Unfortunately, it is undeniable that the resolution of sound is relatively low compared to that of vision in these virtual space illusions. However, while sound is inferior to vision in terms of spatial "resolution", it can provide information that is difficult to present visually in a more intuitive way by allowing us to obtain information "simultaneously" from the "entire" space that surrounds us (Larsson et al., 2007). Michel Chion, known for his audio-visual theory using film as a medium, categorized the sounds of film into (1) in-sound , (2) off-sound , and (3) hors-champ, sounds that are heard inside and outside the field of vision can complement visual information and evoke a sense of "something happening" in the user. Just as you would notice if something happened behind you or above your head when you were reading this, the information provided by sound is both directional and simultaneous, and cannot be mediated by visual information. In terms of immersion in a virtual space, approaches that use not only sight but also hearing are considered to be extremely important.

Sound Design in 3D Space

Two directions were considered for the sound placed in the 3D space: environmental sound and background music. Background music can have a significant effect on the staging of a space, but in this project, as part of the virtual reproduction of the "local ecosystem", we have installed environmental sounds that have been reconstructed based on sound sources actually recorded in the vicinity of the nagaya. Rather than using special recording and editing equipment, we used readily available smartphones (iPhone) and free software (Audacity) to complete the project. Using better microphones and editing software would have allowed us to produce higher quality sound, but the main content of this project was the 3D scanned nagaya and the documentation of the restoration process, so we achieved the lowest possible cost implementation for the sound.

Sight limited to a certain angle, sound that can be heard from any direction

Auditory Experience in VA

The sound you hear when entering the world is actually the sound recorded by opening and closing the sliding doors of the nagaya. The low-frequency range contained in the sound source recorded with the iPhone has been cut, and the focus is on the sound coming from the wooden frame sliding doors with glass. When the door opens, you can hear four footsteps that suggest someone is entering the room. This is also a recording of the sound of actually opening the sliding door of a nagaya and stepping into the dirt floor.

Entrance sound (before processing):

Entrance sound (after processing):

Integrating Environmental Sounds

Two types of sound are placed in the 3D model. On the side of the entrance facing the street, we have placed sounds recorded outside the Inariyu area. We have removed a certain amount of noise, such as the noise made by the refrigerator compressor, and have extracted characteristic sounds such as children's voices and the sound of bicycles, and then added a process to overlap these sounds with the background sounds. The actual processing itself is a simple one that uses the "noise reduction" function built into Audacity.

On the wall facing the bathhouse at the back of the nagaya, we used the sound of the bathhouse that can be heard through the wall. This also uses a sound source recorded in the actual room of the nagaya, and against the background of the sound of running water, you can hear characteristic sounds such as the occasional clashing of bath tubs.

Location of sound sources placed in the world

Although both of these use monaural sound sources, the positioning within the 3D space gives the sound a sense of direction. The sound sources within the 3D space are placed outside the model, and from there they spread out in a concentric circle over a certain range while decaying. As the echoes from the walls are not taken into account, it cannot be said that the acoustic characteristics of a real nagaya are reproduced, but because the direction of the avatar in the space is linked to the direction from which the sound is heard, it can provide a more realistic sense of direction, especially when wearing an HMD.

None of the sounds themselves contain important information, and it would be difficult to say that they function as a medium for conveying knowledge or records. On the contrary, it may not even be clear what the sound is just by listening to it. In some cases, it may not even be noticed that it is playing. However, the important role of sound in this project is to provide the auditory information that we normally unconsciously mobilize in our perception of three-dimensional space within the VR space, and to resolve, even partially, the cognitive discrepancy that exists between reality and the VR space. Therefore, in a sense, it may be important that the sounds enter the ears without even being noticed. In addition, by arranging the sound, a time-based medium, the sense of "time" that flows through the actual nagaya space, or in other words, the sense that "something is happening" is also reproduced in VR. This also contributes to a certain degree to the transparency of the HMD as a medium.

The visual information in this project is contained within the nagaya. On the other hand, the sounds heard within the nagaya are not confined to the interior of the nagaya, but are gently connected to the wider world of the town, region and people that surround the nagaya. The soundscape of this project, which is composed of certain kinds of everyday sounds recorded around the nagaya, is not on the same level as a "realistic reproduction" such as a 3D model in terms of accuracy and reproducibility, but it can be said to play a certain role as a means of conveying the flow of time in the real space and the context of the space surrounding the nagaya. I hope that the introduction of auditory media will emphasize the fact that the Inariyu Nagaya is not an independent entity, but is part of a "local ecosystem" with organic connections.

[References]

- Lombard, Marlize, and Ditton, Theresa, 1997, "At the heart of it all: the concept of presence," Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 3:JCMC321, doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.1997.tb00072.x.

- Larsson, Pontus, Väljamäe, Aleksander, Västfjäll, Daniel, Tajadura-Jiménez, Ana, and Kleiner, Mendel, 2010, "Auditory-induced presence in mixed reality environments and related technology," In The Engineering of Mixed Reality Systems, Emmanuel Dubois, Philip Gray and Laurence Nigay (eds), Springer, London, 143-163, doi: 10.1007/978-1-84882-733-2_8.

- Chion, Michel, 1985, Le Son au Cinéma, Editions de l'Étoile.

Bolter, Jay David and Diane Gromala, 2003, Windows and Mirrors: Interaction Design, Digital Art, and the Myth of Transparency, Cambridge, Mass., MIT Press. - Norman, Donald A., 1999, The Invisible Computer: Why Good Products Can Fail, the Personal Computer is So Complex, and Information Appliances are the Solution, Cambridge, Mass., MIT Press.

Japanese Books on Local Ecosystems (Kohei Suneya)

As mentioned at the outset, this VA (Virtual Archive) was created as part of a collaborative project by the Humanities Center (HMC) of the University of Tokyo. In disseminating information on architectural restoration and regeneration through the VA, one of the key questions was how traditional media, such as books, can be integrated into VR spaces. With this perspective, we decided to use the VR representation of the Inariyu Nagaya to introduce related books. Interestingly, no similar attempts were found during our preliminary research. As a result, we not only identified challenges and opportunities for placing and displaying information of books in VR environments but also addressed fundamental issues concerning the recreation of books in VR spaces and the acquisition and utilization of information for such purposes. This report outlines the workflow and major topics covered in this work, with the aim of serving as a reference for similar future initiatives.

Creating the Book List and Acquiring Book Cover Images

To begin, we compiled a list of books to be displayed in the VA. Given the theme of "restoration and regeneration of Inariyu Nagaya," we identified four relevant topics: (1) sento (public baths), (2) restoration and regeneration of historic buildings, (3) urban lifestyles, and (4) urban history. Based on these themes, the author (Suneya), specializing in sociology and cultural heritage studies, prepared a basic list of references categorized under "public baths," "urban development/renovation," "social and cultural history," and "urban and architectural history." We then sought input from members of Sentou to Machi (Kuryu, Sammonji, and Watanabe) to expand the list. Subsequently, to enhance visibility in the VR space, the category names were shortened to "Public Baths," "Urban Development," "Lifestyles," and "History."

When acquiring and utilizing book cover images, copyright issues needed to be addressed. Copyright law recognizes book covers as copyrighted works if they exhibit originality. In such cases, uploading these images to the internet (e.g. on social media) constitutes "reproduction" and "public transmission," requiring permission from the copyright holder [1]. In practice, publishers' policies vary, but many permit use without explicit permission as long as conditions such as displaying bibliographic information, refraining from modifying images, or notifying publishers (via sample copies or URLs) are met [2].

To streamline the process, we utilized the National Diet Library's (NDL) Book Cover API, which provides images supplied by the Japan Publication Registry Office (JPRO). These images can be used for non-commercial purposes without application, as stated on the NDL website [3]. However, for books not available through the NDL API, we chose not to use publisher website images or scanned book covers, as these would require additional permissions.

Using Books in VR Spaces and Copyright Issues

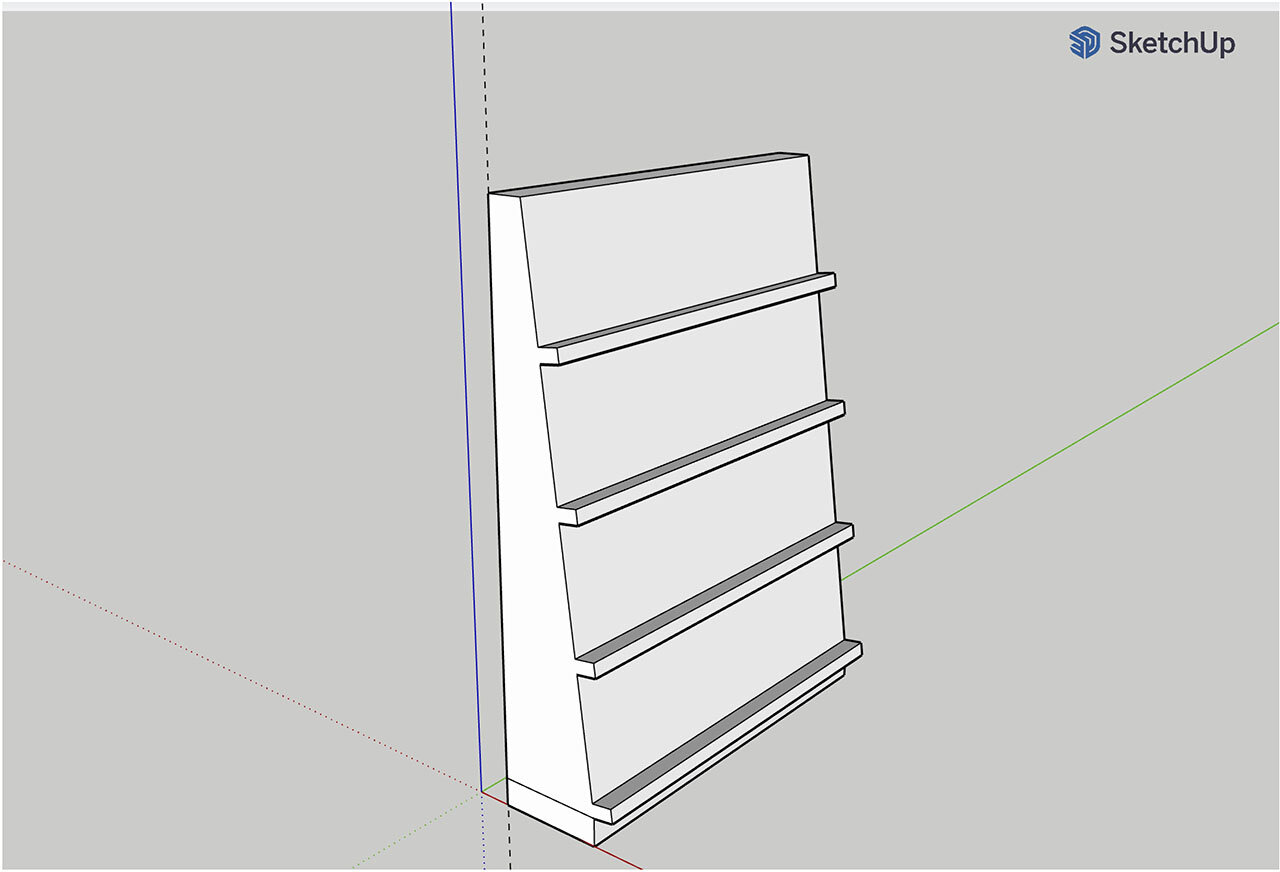

As initially envisioned, a magazine rack-like object with four shelves was to be installed in the VR recreation of the Nagaya's interior to display book information. The design allowed book covers to appear randomly on the shelves. Users could select a shelf to view a list of book covers and bibliographic information categorized into four topics. Selecting a specific book would redirect users to the relevant page of the National Diet Library website. However, several challenges arose, necessitating changes to this concept.

Example of a 3D model of a prototype magazine rack

The first issue was the implementation of links. Since the project operated as a non-profit under the HMC, links to commercial online bookstores were not considered from the outset. During the development process, however, it was discovered that external links could not be implemented within the VR environment. As a solution, the book list and links were decided to be published on HMC's companion website, while the VR space displayed only book cover data and related bibliographic information.

Next, the concept of reproducing a physical bookshelf in VR was reconsidered. As the author became more familiar with Cluster's interface and as prototypes of the book objects were tested, it became clear that VR-specific methods should be prioritized. An alternative proposal involved recreating the appearance of representative books for each category and positioning them within the Nagaya as entry points to the book lists. However, as discussed below, this idea was also ultimately abandoned due to copyright issues.

Initial proposal for book object installation

The final issue concerned copyright and other rights-related problems. While the use of front cover images had already been examined, new concerns emerged regarding the utilization of entire book cover designs when recreating books as 3D objects. Research into precedents revealed discussions on creating 3D scan data of artworks and architectural structures but no examples involving the 3D modeling of book exteriors. Consequently, the issue was examined in two parts: the recreation of books as three-dimensional objects and the use of book cover designs. The former was deemed permissible as the shape of books could be classified as mass-produced items, which, unless they qualify as designs under industrial design law or creative works under copyright law, do not present legal issues. However, for the latter, recreating book covers as 3D objects necessitates utilizing not only the front cover image but also the spine and back cover designs. This would require explicit permission for the entire book cover design. As a result, approaches such as using complete scanned data of book covers or supplementing cover images from APIs with recreated spines and back covers were considered problematic and were excluded.

Final Approach

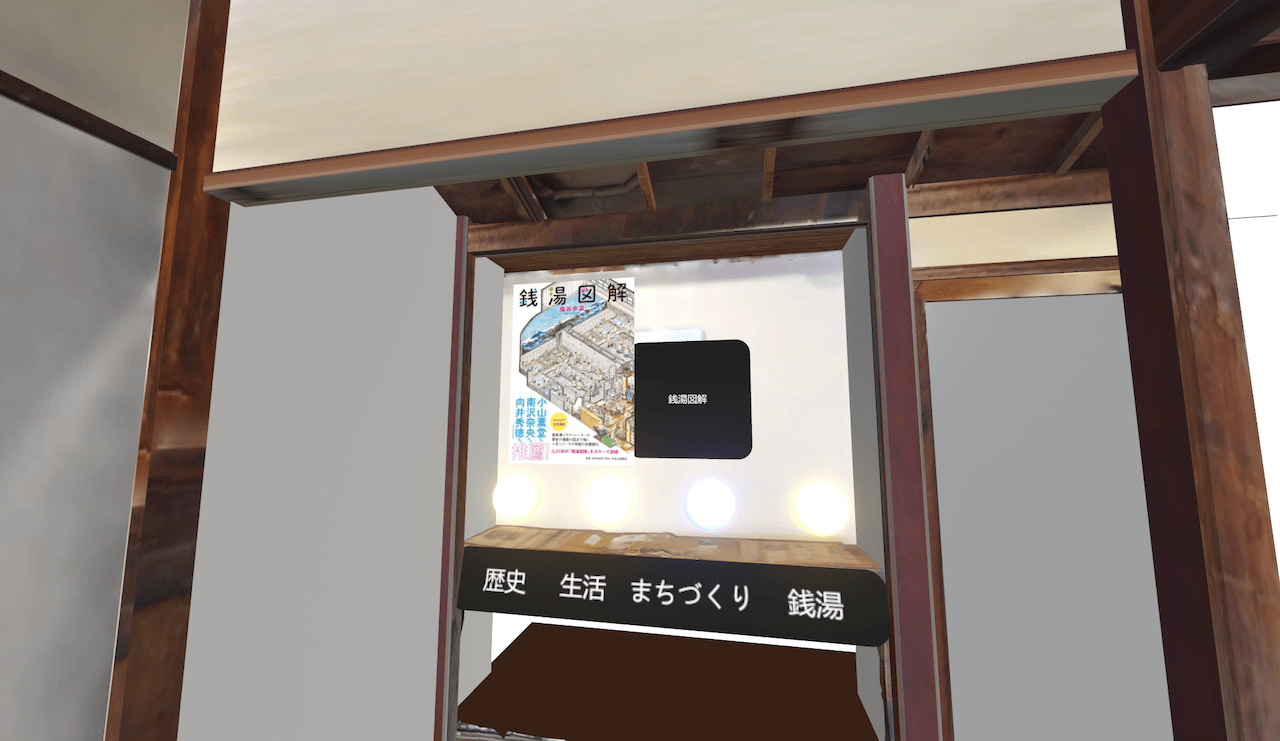

Following these deliberations, two primary measures were implemented. The first involved displaying book covers and bibliographic information as posters within the VR space. Enlarging book covers to poster size and mounting them on walls improved visibility while allowing users to switch displayed content instantaneously via button operations. This approach not only leveraged the unique characteristics of VR but also harmonized the displays with the overall interior aesthetic. The display was placed on the wall at the back of the tatami room, where books and photos are exhibited in the actual Nagaya. Four floating, illuminated buttons were added; each button, when pressed, displayed book covers and titles corresponding to one of the four categories. Holding down a button allows users to cycle through random book displays.

Final adopted proposal for the layout of the book covers

The second measure was the creation of a 3D object representing the "Inari-yu Restoration Project Report". With permission from Sento to Machi, the copyright holder, the report's cover design was used to create a 3D object. Photos from the report, including images of the Nagaya's exterior and interior as well as its use as a third place, were incorporated. When users interact with the 3D object, the photos are displayed via the UI. This measure not only serves as an attempt to reproduce books as physical objects in VR but also functions to convey supplemental information related to the Nagaya restoration and regeneration project through the VR space.

Example of display of image from the "Inari-yu Restoration Project Report"

"Inari-yu Restoration Project Report" installed as a 3D object

Conclusion

This project highlighted the importance of clear objectives, understanding the nature of information, and assessing technical feasibility during the planning and implementation of VR features. As someone unfamiliar with VR technologies, the author collaborated with Panda Mogura and other team members to align objectives and methodologies. Nonetheless, future projects would benefit from planners with greater expertise in VR utilization and implementation.

Additionally, the lack of clear guidelines on the use of book cover designs in VR environments posed challenges. This issue, which became evident as our original plans required modifications, underscores the need for clearer standards regarding the use of book appearances and shapes.

While VR offers exciting opportunities to transcend physical limitations, it also demands adherence to real-world copyright and licensing requirements. There remains significant potential for synergy between the humanities and VR, provided that these challenges are addressed.

[References]

[1]澤田将史(2023)「図書館における書影等の利用」『情報の科学と技術』73(8), 346-352.

[2]岩波書店「よくあるお問い合わせ 書影(表紙画像)のご利用」(最終閲覧日:2024年10月13日)

[3]国立国会図書館サーチ「17.APIのご利用について」(最終閲覧日:2024年10月13日)

[4]五常総合法律事務所(2017)「クローン文化財と3Dデータの著作権」(最終閲覧日:2024年10月14日)

[5]関真也法律事務所(2022)「【メタバースの法律《著作権×クリエイターエコノミー》】他人の作品を3Dスキャンしたデータをメタバースで販売することは許されるのか?」(最終閲覧日:2024年10月14日)

[6]慶應義塾大学SFC研究所ファブ地球社会コンソーシアム(2015)「WG2「3Dデータ流通とコンテンツ創造」 2015 年度報告書 3Dデータをめぐる権利とビジネスモデル」(最終閲覧日:2024年10月14日)

Recommended Japanese Books

江戸東京の都市組織に挑む:上野 本郷 谷中 根津 下谷 、2019、法政大学江戸東京研究センターほか 編著、彰国社

江戸東京の都市組織に挑む:上野 本郷 谷中 根津 下谷 、2019、法政大学江戸東京研究センターほか 編著、彰国社 水都としての東京とヴェネツィア:過去の記憶と未来への展望 、2022、法政大学江戸東京研究センター 編、法政大学出版局

水都としての東京とヴェネツィア:過去の記憶と未来への展望 、2022、法政大学江戸東京研究センター 編、法政大学出版局 建築をつくるとは、:自ら手を動かす12人の仕事 、2024、河野直ほか 編著、学芸出版社

建築をつくるとは、:自ら手を動かす12人の仕事 、2024、河野直ほか 編著、学芸出版社 中村達太郎 日本建築辞彙〔新訂〕 、2011、太田博太郎・稲垣栄三 編、中央公論美術出版

中村達太郎 日本建築辞彙〔新訂〕 、2011、太田博太郎・稲垣栄三 編、中央公論美術出版 東京わが残像 1948-1964 、2017、田沼武能、クレヴィス

東京わが残像 1948-1964 、2017、田沼武能、クレヴィス-

明治の東京計画 、2004、藤森照信、岩波書店

明治の東京計画 、2004、藤森照信、岩波書店  江戸・東京の都市史:近代移行期の都市・建築・社会 、2014、松山恵、東京大学出版会

江戸・東京の都市史:近代移行期の都市・建築・社会 、2014、松山恵、東京大学出版会 建築探偵術入門 新装版 、2014、東京建築探偵団、文藝春秋

建築探偵術入門 新装版 、2014、東京建築探偵団、文藝春秋 みる・よむ・あるく東京の歴史 7 、2019、池享ほか 編、吉川弘文館

みる・よむ・あるく東京の歴史 7 、2019、池享ほか 編、吉川弘文館 地形で見る江戸・東京発展史 、2022、鈴木浩三、筑摩書房

地形で見る江戸・東京発展史 、2022、鈴木浩三、筑摩書房 東京史:七つのテーマで巨大都市を読み解く 、2023、源川真希、筑摩書房

東京史:七つのテーマで巨大都市を読み解く 、2023、源川真希、筑摩書房 定点写真で見る東京今昔 、2024、鷹野晃、光文社

定点写真で見る東京今昔 、2024、鷹野晃、光文社 建築の絵本 東京のまちづくり : 近代都市はどうしてつくられたか 、1986、藤森照信・小澤尚、彰国社

建築の絵本 東京のまちづくり : 近代都市はどうしてつくられたか 、1986、藤森照信・小澤尚、彰国社- 東京の空間人類学 、1992、陣内秀信、筑摩書房

- 日本の都市空間 、1984、都市デザイン研究体、彰国社

- 建築の多様性と対立性 、1982、R.ヴェンチューリ 著・伊藤公文 訳、鹿島出版会

- 見えがくれする都市 、1980、槙文彦ほか 他、鹿島出版会

- 東京都市計画物語 、2001、越澤明、筑摩書房

- 東京の原風景 、1979、川添登、日本放送出版協会

- 民家のみかた調べかた 、1967、太田博太郎 編・文化財保護委員会 監修、第一法規出版

- 古建築調査ハンドブック 、2021、山岸常人・岸泰子・登谷伸宏、勉誠社

- 東京建築遺産さんぽ 、2019、大内田史郎 著・傍島利浩 写真、エクスナレッジ

- 世界の都市の物語12 東京 、1992、陣内秀信、文芸春秋

楽しい縮小社会:「小さな日本」でいいじゃないか、2017、森まゆみ・松久寛、筑摩書房

楽しい縮小社会:「小さな日本」でいいじゃないか、2017、森まゆみ・松久寛、筑摩書房 落語がつくる<江戸東京>、2023、田中優子 編、岩波書店

落語がつくる<江戸東京>、2023、田中優子 編、岩波書店 絶滅危惧個人商店、2024、井上理津子、筑摩書房

絶滅危惧個人商店、2024、井上理津子、筑摩書房 東京の生活史、2021、岸政彦 編、筑摩書房

東京の生活史、2021、岸政彦 編、筑摩書房 新・江戸東京研究の世界、2023、法政大学江戸東京研究センター 編、法政大学出版局

新・江戸東京研究の世界、2023、法政大学江戸東京研究センター 編、法政大学出版局 もんじゃの社会史:東京・月島の近・現代の変容、2009、武田尚子、青弓社

もんじゃの社会史:東京・月島の近・現代の変容、2009、武田尚子、青弓社 趣都の誕生:萌える都市アキハバラ、増補版、2008、森川嘉一郎、幻冬舎

趣都の誕生:萌える都市アキハバラ、増補版、2008、森川嘉一郎、幻冬舎 盛り場はヤミ市から生まれた 増補版、2016、橋本健二・初田香成 編著、青弓社

盛り場はヤミ市から生まれた 増補版、2016、橋本健二・初田香成 編著、青弓社 浅草公園凌雲閣十二階 : 失われた〈高さ〉の歴史社会学、2016、佐藤健二、弘文堂

浅草公園凌雲閣十二階 : 失われた〈高さ〉の歴史社会学、2016、佐藤健二、弘文堂 まちあるき文化考 : 交叉する〈都市〉と〈物語〉、2019、渡辺裕、春秋社

まちあるき文化考 : 交叉する〈都市〉と〈物語〉、2019、渡辺裕、春秋社 東京裏返し:社会学的街歩きガイド、2020、吉見俊哉、集英社

東京裏返し:社会学的街歩きガイド、2020、吉見俊哉、集英社 東京ヴァナキュラー : モニュメントなき都市の歴史と記憶、2021、ジョルダン・サンド(池田真歩 訳)、新曜社

東京ヴァナキュラー : モニュメントなき都市の歴史と記憶、2021、ジョルダン・サンド(池田真歩 訳)、新曜社 神田神保町書肆街考、2022、鹿島茂、筑摩書房

神田神保町書肆街考、2022、鹿島茂、筑摩書房- 都市空間のなかの文学、1982、前田愛、筑摩書房

- 「民都」大阪対「帝都」東京 : 思想としての関西私鉄、1998、原武史、講談社

- 路上観察学入門、1986、赤瀬川原平ほか 編、筑摩書房

- 都市民俗学 : 都市のフォークソサエティー、1990、小林忠雄、名著出版

- 荷風随筆集. 上、日和下駄 : 他16篇、1986、永井荷風 著・野口冨士男 編、岩波書店

- 新編東京繁昌記、1993、木村荘八、岩波書店

- 広告都市・東京 : その誕生と死、増補、2011、北田暁大、筑摩書房

- 東京遺産:保存から再生・活用へ

、2003、森まゆみ、岩波書店

、2003、森まゆみ、岩波書店 - 都市再生・街づくり学:大阪発・民主導の実践

、2008、大阪市街地再開発促進協議会 編、創元社

、2008、大阪市街地再開発促進協議会 編、創元社 - アメリカ大都市の死と生 新版

、2010、ジェイン・ジェイコブズ(山形浩生 訳)、鹿島出版会

、2010、ジェイン・ジェイコブズ(山形浩生 訳)、鹿島出版会 - 〈鞆の浦〉の歴史保存とまちづくり:環境と記憶のローカル・ポリティクス

、2016、森久聡、新曜社

、2016、森久聡、新曜社 - 時がつくる建築:リノべーションの西洋建築史

、2017、加藤耕一、東京大学出版会

、2017、加藤耕一、東京大学出版会 - 町並み保存運動の論理と帰結:小樽運河問題の社会学的分析

、2018、堀川三郎、東京大学出版会

、2018、堀川三郎、東京大学出版会 - 建築と都市の保存再生デザイン:近代文化遺産の豊かな継承のために

、2019、田原幸夫ほか 編著、鹿島出版会

、2019、田原幸夫ほか 編著、鹿島出版会 - 古いのに新しい! リノベーション名建築の旅

、2019、常松祐介、講談社

、2019、常松祐介、講談社 - リノベーションからみる西洋建築史:歴史の継承と創造性

、2020、伊藤喜彦ほか、彰国社

、2020、伊藤喜彦ほか、彰国社 - ダッチ・リノベーション:オランダにおける建築の保存再生

、2021、笠原一人、鹿島出版会

、2021、笠原一人、鹿島出版会 - アーバニスト:魅力ある都市の創生者たち

、2021、中島直人・一般社団法人アーバニスト、筑摩書房

、2021、中島直人・一般社団法人アーバニスト、筑摩書房 - 銭湯から広げるまちづくり:小杉湯に学ぶ、場と人のつなぎ方

、2023、加藤優一、学芸出版社

、2023、加藤優一、学芸出版社 - 株式会社黒壁の起源とまちづくりの精神、2009、角谷嘉則、創成社

- いきている長屋 : 大阪市大モデルの構築、2013、谷直樹・竹原義二 編著、大阪公立大学共同出版会

- 「谷根千」の冒険、2002、森まゆみ、筑摩書房

- エンジョイ、レトロビル!未来のビンテージビルを創る、2009、スペースRデザイン、書肆侃侃房

入浴の女王 新装版、2012、杉浦日向子、講談社

入浴の女王 新装版、2012、杉浦日向子、講談社 テルマエと浮世風呂:古代ローマと大江戸日本の比較史、2022、本村凌二、NHK出版

テルマエと浮世風呂:古代ローマと大江戸日本の比較史、2022、本村凌二、NHK出版 銭湯(NHK美の壺)、2009、NHK「美の壺」制作班 編、日本放送出版協会

銭湯(NHK美の壺)、2009、NHK「美の壺」制作班 編、日本放送出版協会 おふろやさん、1977、西村繁男、福音館書店

おふろやさん、1977、西村繁男、福音館書店 ゆ場、2022、柳原美咲、冬青社

ゆ場、2022、柳原美咲、冬青社 湯屋番五十年 銭湯その世界、2006、星野剛、草隆社

湯屋番五十年 銭湯その世界、2006、星野剛、草隆社 銭湯検定公式テキスト. 1、2009、日本銭湯文化協会 編、草隆社

銭湯検定公式テキスト. 1、2009、日本銭湯文化協会 編、草隆社 ひつじの京都銭湯図鑑、2016、大武千明、創元社

ひつじの京都銭湯図鑑、2016、大武千明、創元社 近代日本の公衆浴場運動、2016、川端美季、法政大学出版局

近代日本の公衆浴場運動、2016、川端美季、法政大学出版局 銭湯は、小さな美術館、2017、ステファニー・コロイン、啓文社書房

銭湯は、小さな美術館、2017、ステファニー・コロイン、啓文社書房 銭湯図解、2019、塩谷歩波、中央公論新社

銭湯図解、2019、塩谷歩波、中央公論新社 銭湯空間、2020、今井健太郎、KADOKAWA

銭湯空間、2020、今井健太郎、KADOKAWA 懐かしくて新しい「銭湯学」:お風呂屋さんを愉しむとっておき案内、2021、町田忍 監修、メイツユニバーサルコンテンツ

懐かしくて新しい「銭湯学」:お風呂屋さんを愉しむとっておき案内、2021、町田忍 監修、メイツユニバーサルコンテンツ- ザ・東京銭湯、2009、町田忍 編、戎光祥出版

- いま、むかし・銭湯(Inax booklet ; vol.8 no.1)、1988、Inaxギャラリー企画委員会 企画、Inax東京ショールーム

- 風呂のはなし (物語ものの建築史)、1986、大場修、鹿島出版会

- 銭湯文化的大解剖! : まちのお風呂屋さん探訪、2021、おしどり浴場組合 編、神戸新聞総合出版センター

- 銭湯へ行こう、1992、町田忍 編著、TOTO出版

- 関西のレトロ銭湯、2009、松本康治 写真・文、戎光祥出版

- いらっしゃい北の銭湯、1998、塚田敏信、北海道新聞社

- テルマエ・ロマエ 1、2009、ヤマザキマリ、エンターブレイン

- 社会的共通資本、2003、宇沢弘文、岩波書店

- 銭湯遺産、2008、町田忍 写真・文、戎光祥出版

- CONFORT 193号 2023年10月(特集 風呂という冒険)、2023、建築資料研究社

- "文化財研究紀要. 別冊 (通号32)、2024年3月 銭湯「稲荷湯」「春日湯」「殿上湯」調査報告書"、2024、、東京都北区教育委員会

- 最後の銭湯絵師:三十年の足跡を追う、2013、町田忍、草隆社

- 銭湯と横浜、2018、横浜開港資料館・横浜市歴史博物館 編、横浜市ふるさと歴史財団

- レトロ銭湯へようこそ:関西版、2015、松元康治 写真・文、戎光祥出版

- レトロ銭湯へようこそ:西日本版、2017、松元康治 写真・文、戎光祥出版

- 消費をやめる 銭湯経済のすすめ、2014、平川克美、ミシマ社

- 絵で見るお風呂の歴史、2009、菊地ひと美

Street Scanning (Ikki Ohmukai)

The townscape scanning was carried out as a sub-project of this research, with the aim of recording the changing state of the environment around Inariyu. 3D scanning of the interior of buildings can be carried out systematically because the measurement area is clear and it is possible to control the movement of people and the brightness of the room. Outdoors, on the other hand, it is difficult to define the area to be scanned and it is not possible to restrict the movement of passers-by. In addition, there are factors such as the brightness of the environment changing moment by moment due to the weather and the passage of time, and it is difficult to digitise with high accuracy. For this project, we prioritised ease of use over accuracy, and introduced a workflow that minimised time spent on site using relatively inexpensive equipment. This time, with the help of TCN, we were able to compare the differences in accuracy by simultaneously measuring with a 3D laser scanner (Matterport Pro 3) for outdoor commercial use.

Photogrammetry is a widely used method for creating 3D models without using a dedicated 3D scanner. Photogrammetry is a technique that extracts common points from a large number of images taken with a digital camera and estimates the 3D shape of the object. In recent years, a technique called 3D Gaussian Splatting has also attracted attention as a more advanced method of generating 3D data. To model a 3D object with a side of a few tens of centimetres using photogrammetry, you need tens or hundreds of images, but the road around Inariyu, the subject of the photo, is 30 metres long, so it would take a huge amount of time to photograph it all. So we decided to record a video with a camera capable of 360-degree photography (Insta360 ONE RS 1-inch 360-degree version), and then use automatic processing to extract a large number of images from the video for photogrammetric processing. When scanning outdoors, height information is also important. Normally, this is often done using a drone, but this is not practical because it requires expensive equipment and the use of drones is strictly limited in Tokyo. In this case, we attached a camera to a 3m-long rod-shaped device and took photos from a high vantage point. This is difficult to achieve with an expensive 3D scanner, and it could be an advantage to use consumer equipment.

From the two 360-degree video files, which were shot from different heights and lasted about 90 seconds, we extracted about 2,700 images and used Agisoft's Metashape to process them using photogrammetry. We also used Epic Games' RealityCapture and Jawse's Postshot to perform 3D Gaussian blending on the same set of images. The photogrammetry was performed on a mobile laptop (MacBook Air M2) and the 3D Gaussian splatting on a gaming laptop with relatively high image processing power.

The accuracy of the 3D models produced by the two methods and the 3D model produced by Matterport Pro 3 is clearly higher for the latter, and the data produced by the former cannot be said to be of sufficient quality to be used in a clustered environment, etc. However, it does provide the minimum functionality for the purpose of recording environments, and the significance of being able to achieve this kind of work with photographic equipment costing less than 100,000 yen and a standard PC is significant. With the commoditisation of the technology, it is expected that the 'democratisation' of 3D capture will progress rapidly, with applications enabling 3D modelling and 3D modelling using only a smartphone.

Street Scanning

Inariyu Nagaya VA Content Management System (CMS) (Jun Ogawa)

The Inariyu Nagaya Restoration and Revitalisation VA Project (hereafter, Inariyu VA) will end in August 2024, but we will also work on presenting an archiving model that organizes the main work done and the data used or created in this project.

3D/VR Contents and the Archiving

The use of 3D/VR technology in the context of historical and cultural spaces and assets for research, education and public experience is developing rapidly and involves a range of fields including museum studies, archaeology and history, as well as information studies and media design. For example, in the field of digital humanities, which explores the ways in which the humanities and computer science can be combined, there are now various attempts to (re)-construct historical urban spaces and objects as 3D and to gain new insights from them. And many of these projects, including our Inariyu VA, are creating multimodal content that links 3D models with various contextual information. UrbanHistory4D, which overlays 3D urban spaces with old photographs, and PURE3D, which explores new forms of digital storytelling through multimodal annotation of 3D models, are good examples.

As the creation of exciting works progresses, the importance of archiving the process of content creation and the data it generates is also becoming widely recognised. For example, the term 'paradata' is often used in the context of 3D usage in the digital humanities. Generally defined as 'data related to the interpretation made during the process of generating data', paradata is based on the idea of recording all the information generated during the process, rather than the data itself as a finished product. The importance of paradata in data visualization, especially in virtual spaces, is also emphasized by many research institutions and projects conducting advanced research in the West. In the Inariyu VA Project, the term 'paradata' is not explicitly used, but we aim to record and make available for sharing as much as possible of the various tasks carried out during the process of building the metaverse space, as well as the materials and data used and created during this work.

Content Management with Omeka S

In the actual archiving work, it is necessary to record 1) 'actions' in the sense of some kind of work in the research process, and 2) 'data' used in the 'action' or generated as a result of the 'action'. In this way, a set of information consisting of these 'actions' and 'data' is often conceptualized in the context of research data management as a 'data flow' or 'data lifecycle.' The ultimate goal of the archiving in this project is, of course, to record the entire data flow. However, it is clear that recording the various 'actions' as digital data is an extremely difficult task. For this reason, in this project we have decided to start by archiving the 'data' resources, such as images and audio, that were used and generated in the process of building the metaverse environment rather than 'actions.'

In recent years, many digital archives have begun to use content management systems (CMS) to manage their resources. In this project we have chosen to use Omeka S, one such CMS, to manage our multimodal information resources. Omeka S is an open source CMS developed at the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media at George Mason University, and is widely used to manage digital collections at many GLAM institutions in Japan and overseas. We aim to build a versatile and extensible archive using Omeka S, which can be extended with a wide range of plug-ins, including support for IIIF, an international standard for sharing image and video data, and which can be used to distribute and display content without high skills and knowledge of web application development.

The types of resources to be archived in this project are mainly 1) 3D models, 2) photographs and images, and 3) audio. 1) include scanned models of the house itself and cityscapes created using Matterport and other softwares, as well as models that have been processed for use in the metaverse. 2) include photographs of the site taken during the physical restoration or the 3D scanning of the house, and some drawings posted in the metaverse space to inform users, and 3) includes raw data of everyday life sounds recorded on site, as well as audio data processed for use in the metaverse.

As these data resources were created by different people, we first used Dropbox, a cloud data service to consolidate the data. We then manually uploaded them to the system from the Omeka S administrator dashboard and registered the items with basic metadata such as creator and creation date. At this moment, we use the default Dublin Core metadata schema. Of course, you can also register other schemas including customized ones, giving you the flexibility to handle information that cannot be described by existing schemas, if necessary. Below is a screen for registering an image depicting us scanning the cityscape as an item, and the basic information attached to it.

Editing screen for metadata in Omeka S

In this way, by adding the required metadata to the resources collected and registering them as items, it is possible to represent the contents (in the case of images, in accordance with IIIF) as a digital archive, albeit a very simple one. This alone makes it a fully functional environment for recording, searching and viewing the resources and data used and generated in the project.

IIIF image and metadata display using Omeka S

In addition, Omeka S also allows you to link items together, so you could, for example, link a recorded audio to a photograph taken during the recording process, that enables you to keep the context of its creation. Alternatively, you could link images or videos used to create a 3D model to the model itself and display them as metadata for the 3D model creation process. At the moment the archiving activities of this project are limited to the stage of registering resources in Omeka S and adding basic metadata, or in other words the stage of building a 'data' poll, but in the future we would like to work towards an archive that includes 'actions' by mainly exploring methods of describing the semantic relationships between items.

Conclusion

The archiving concept and model presented by this project is so far only one 'model of' the Inariyu VA, but we will continue to consider how it can contribute to the future use of the Nagaya and to make it a more useful 'model for' anyone working on similar activities.

Intellectual Property Rights for this Project

Companion Site

HMC Collaborative Research "Digital Platform for Cultural Resources for Open Humanities Inariyu Nagaya Restoration and Regeneration Virtual Archive Companion Site by "Inariyu Nagaya Restoration and Regeneration Virtual Archive" Production Team is licensed under CC BY 4.0

The world for VA is subject to the cluster terms of use. Please refer to Article 16, "Rights Ownership" in particular. However, when taking screenshots of the images and text of the Inariyu Nagaya Restoration Project shown on the world (VA), please use them with the credit for "Sentoutomachi" and the credit for the photographer shown in the lower right of the photo.

Inariyu Tenement House Restoration and Regeneration Virtual Archive

Please review the description of intellectual property in the Inariyu Tenement House Restoration and Regeneration Virtual Archive.

Member

- Ikki Ohmukai (Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology, The University of Tokyo)

- Jun Ogawa (Doctoral Program, Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology, The University of Tokyo; Specially Appointed Researcher, Digital Content and Media Sciences Research Division, National Institute of Informatics)

- Kohei Suneya (Doctoral Program, Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology, The University of Tokyo)

- Mariko Kasahara (Assistant Professor, Humanities Center)

- Panda Mogura (VR artist)

- Rikutaro Manabe (Graduate School of Engineering, The University of Tokyo / Center for the Advancement of Higher Education)

- Seishi Watanabe (Doctoral Program, Faculty of Engineering and Design, Hosei University; Sento to Machi)

- Shintaro Seki (Doctoral Program, Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology, The University of Tokyo)

- Takako Fujimoto (Doctoral Program, Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology, The University of Tokyo; Teaching Assistant, Department of Architecture, Faculty of Engineering and Design, Hosei University; Certified Archivist)

- Yusuke Nakamura (Graduate School of Humanities and Sociology, The University of Tokyo): Collaborative Project Representative

Acknowledgements

In creating the VA, we received research materials from Sentō to Machi, which also provided full cooperation in our collaborative project.

Cluster Corporation has exceptionally allowed us to use their services free of charge as a "research activity."

For the cityscape scanning, Tokyo Cable Network offered us the valuable opportunity to participate in the scanning using the latest equipment. The survey, restoration and creation of the archive for Inariyu Nagaya were made possible thanks to the deep understanding of the Tsuchimoto family, the owners of the nagaya. In addition, the additional townscape scans were carried out with the cooperation of the neighbors of the Inariyu Nagaya area.

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all of them for their generous cooperation.